In those days when he was copying Rembrandts at the Met, he went about it as closely as he could to approximate the techniques of the 16th and 17th centuries. Following an incredible little book, rich with The Secret of the Old Masters by Albert Abendschein (D. Appleton and Company, © 1916 ), he ground his own paints with mortar and pestle, added the various mediums, gessoed his work surfaces, then built up such paintings by layering one tint placed over another: he under-painted in dark tones as did Rembrandt, then picked up these portraits with grays and whites,

and lastly laid on his layers of colors. Then glazed, varnished. I still have this book with Andy’s annotations regarding the painting of flesh tones. And that glass pestle.

Now he had to begin work in his chosen field and he had to produce a portfolio. Though I did not know him back then, I do recall him mentioning Fredman-Chaite, so I am guessing that was one studio he approached when seeking a job as an apprentice. I do not know what he showed them in order to display his own talent and dedication to art. Or if he only told him of his art education.

What he landed was a job at Cooper Studios some time in 1951 as an apprentice for their fabulous group which included stars like Joe de Mers, Jon Whitcomb, Joe Bowler. Andy cleaned their palettes, their brushes, acted as all apprentices in art studios: they were errand boys, cutting mats, probably delivering jobs, a veritable "gofer." But he was observing everything about this commercial art business. Apparently he especially befriended Joe de Mers whose work he admired. And de Mers kindly took Andy under his wing and loaned him his own photos with which to create his samples. Again, we have the pattern of Andy’s life: working late into the nights alone at his art. He did this at Cooper.

Also while he was there, and I am guessing it was only about a year or so before he built up his own portfolio, it seems there was a young woman who worked there, too. She appeared and disappeared from time to time. (I never got the impression from Andy that she was one of the artists. When he spoke to me of her, his recollection was of her casually washing the eternal coffee cups that everyone used.)

It turned out that this woman had tuberculosis, about which not enough was understood . Certainly, not by the general public. Suffice it to say, in those days, prior to 1952 , there was no real cure for it. It was called "arrested," at best, when in pulmonary tb the scar tissue built up over the diseased area[s] in the affected lung, and the fever abated, as did the cough, and the night-sweats. So she worked some of the time -- until she fell ill again. Then, a while later, she would return to work.

At that time, Andy was ready to strike out on his own. And we return to that rainy "Autumn in New York" afternoon in 1952 when he walked into Rahl Studios for the first time. And was promptly taken on as a member of that ‘stable’ of artists.

There were about 16 – 20 people there. I am not sure of the exact number. Several of the artists worked in the NYC studio which was made up of a series of partitioned cubbyholes for the artists. I think it was on the 14th floor of the French Building.

(Later, they moved nearby to 45 West 45th Street to a larger spread.) Those artists who utilized ‘in house’ space worked off a 60/40 percent commission. Those who worked from home gleaned a larger cut at 70/30 percent. There were several artists who commuted from such places as Norwalk and Westport, Connecticut and a couple came from Pennsylvania to New York City when their jobs were ready to be delivered by the sales staff. Rahl had a brother-in-law, Leo Vallen, as one of his salesmen; there was Norm Heffron, Roland Galen, (the latter two dealt more with out-of-town clients) Phil Rahl, of course (when he was in town from his Black Angus farm in Washingtonville, New York) and his extremely competent studio manager, Willard Seymour.

There were about three apprentices, one of whom -- George Walowen -- ultimately moved up to do artwork and/or sales (I’m not certain if it was both or just the one ) and there was Vinny Dwyer, I recall . Also with artistic talent. They delivered the art, cut the mats, prepared the samples from tear sheets which the sales staff would take around to the agencies and magazines. And in slow times between jobs, an artist would work up fresh samples for the salesmen to use to drum up business. There was the Costume Researcher (in later years they were dubbed Fashion Coordinators), myself who booked the models, obtained whatever any of the artists needed for their jobs, props from skis to peignoirs, period costumes, photos rented from Bettman-Archives or from the N.Y. Public Library. Sometimes it ranged from Victorian love seats to Eames chairs, and frequently clothes for the models who rarely had what we needed. One quickly learned to have a back-up outfit even when models said they had what we asked for. You could not waste time on a shoot if the clothes they brought were no good. You had to proceed, full tilt, regardless. Likely the clock was ticking on another model hired on that same job. Or another photo session was scheduled immediately after. Often clothes were purchased by me ahead of time just for the shoot and then returned to the department stores ASAP so the artists didn’t have to incur more expenses than they already had.

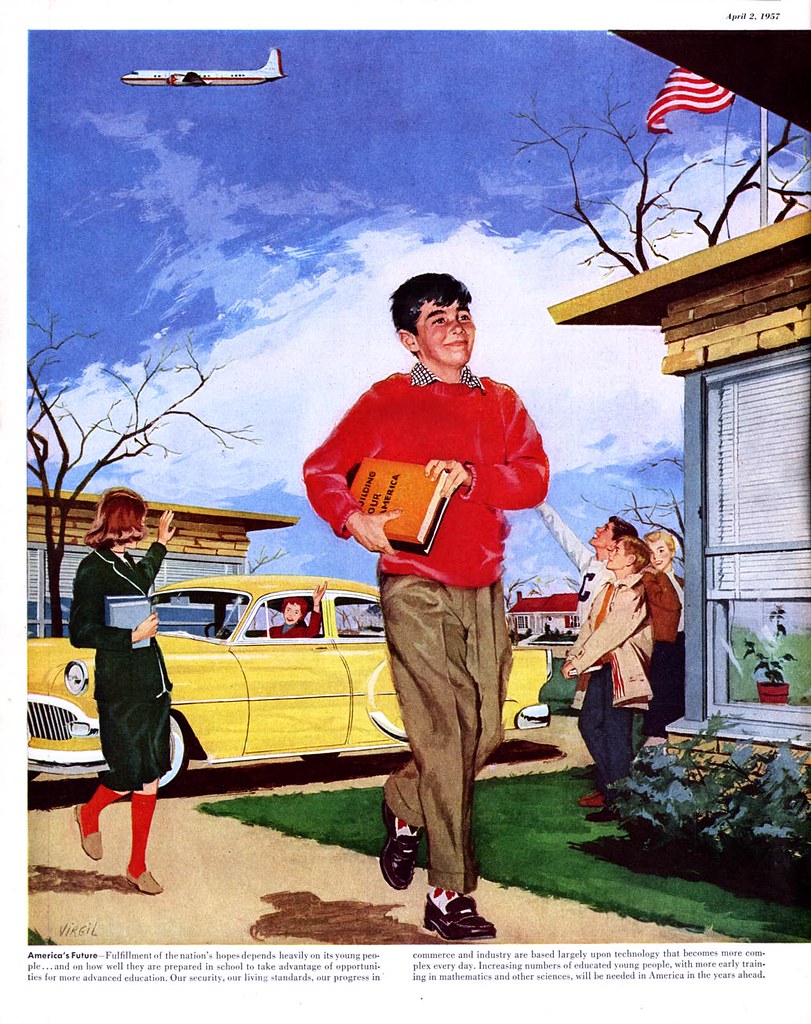

At this point it is interesting to note that all expenses for models (and prop rentals on a job) came out of the illustrators’ commissions. At the same time, the practice for New York photographers was to bill the clients for all this! I was incensed to learn of this inequity, and the artists often complained mightily about how unfair it was. But they did nothing about fighting it. Because of these costs, whenever possible, artists would use their own possessions for props, or take photos within their homes and use family or friends to pose for them. Much that appeared in Andy’s work came from our home. Including our felines and our Irish setter who was in this Dobbs hat ad,

our antiques and my clothes and my homemade curtains. And from 1963 on, our daughter! Many times over. (Her rates were reasonable.)

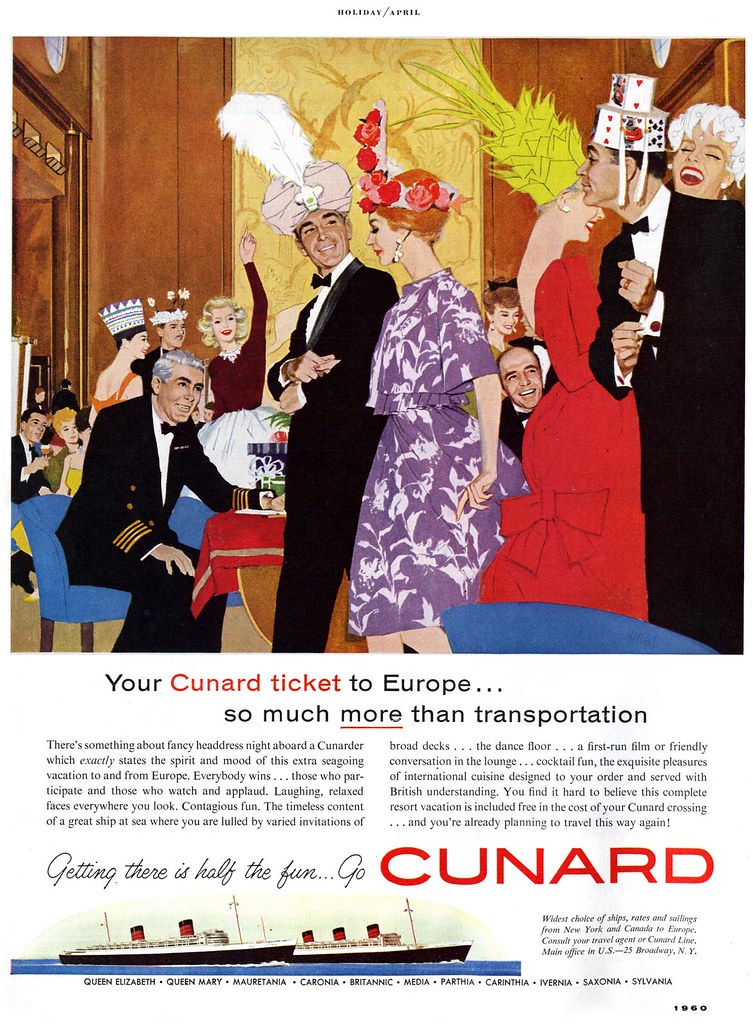

In my ‘spare’ time I maintained a "scrap" file on every imaginable subject clipped from magazines. The scrap served the artists and was often incorporated into their illustrations via the "Lucy" (or camera lucida, that mainstay of the commercial artist) when they had to place photos of their posed models on shipboard or in a country setting, in a ballroom,

or in a factory or a kitchen, bedroom , etc. Last, but key as all were for the functioning of Rahl Studios, was a secretary /receptionist/ bookkeeper.

Some of the artists and/or those who were added on in the years I was there included Fred Siebel, Dorothy Monet, Oskar Barshak, Robert Patterson, Leo "Dink" Siegel, Phil Dormont, Ben Prins, Boomy Valentine, Al Muenchen, Raphael Cavalier, Herb Saslow, Roy Cragnolin, and later Fred Otnes and Arpi Ermoyan were added. There was a single photographer, Jerry Kornblau. (He, much later, opened his own antique shop in the city catering to such as Andy Warhol.)

It seemed to me as an outsider that, generally speaking, these people each had their own illustration niche and hence were not in close competition with one another. Once in a while, though, if an artist was chosen by a client but was too booked up with other work, a salesman might in those early years offer as a substitute someone like Dorothy to fill in for Andy. Or Siebel who originated "Mr. Clean" right there at Rahl in the ’50s , or possibly Muenchen could fill in for Dink Siegel’s semi-cartoon animated figures. That sort of thing. I don’t recall this happening often though. Muenchen, an incredible talent whom Andy liked a great deal, was the car man. In a pinch, if Muench was unavailable, Roy Cragnolin might fill in for him. Another artist Andy particularly enjoyed was Fred Siebel, a brilliant, complex and multifaceted individual. Dink Siegel was loved by all – especially by all the models! If they were lost sight of between posing for a job and coming out to the front desk to get paid, one only need go back to Dink’s cubicle and there they would be. Dink was a genuinely sweet laid-back fellow – and a chick magnet. Our in-house balding but crew-cut bachelor, a Gary Cooper type, with a slender hooked nose. And he was also one of Andy’s poker buddies. Dorothy Monet was a rare charmer with friends in theater and movies like Shelley Winters, Robbie and John Garfield, the Lee Strassburgs whose daughter Susan visited the studio one day for she was interested in commercial art, Clifford Odets, Artie Shaw. Dorothy was a beauty of many talents. Decades later, I was stunned to see that it was she who wrote the tv script for a fine production on the artist Mary Cassatt for PBS.

3 comments:

This is how it goes. Great illustrations! Thank you Anita for revealing all this to us. His and your lives.

My dad George WIthers worked at Rahl Studios in the 1940s. I'm sure that Phil Rahl got my dad illustration jobs for stories in the Saturday Evening Post in 1943, some of which were published in 1944 after my dad entered the army. One illustration in particular comes to mind. It was for "Both Parties Concerned" by J.D. Salinger. in the story the main character Billy dreams that he is also "Sam" the piano player from the film "Casablanca." My dad painted himself twice for the illustration - once as Billy having a drink and a cigarette in an easy chair, and once as "Sam," a ghostly image of a piano player. My dad used himself as a model for many of his illustrations. Thanks, Brian Withers brianwith@gmail.com

nice part of some of the history thank you..........John Ethan Rahl

Post a Comment